When Natan Obed was a teenager, he played on a high school hockey team called the Indians. His school was located next to a reservation in rural Maine, but almost none of its students were Indigenous. Obed is Inuk—he grew up in Nunatsiavut, along Labrador’s Arctic shore—so he stood out, especially on the ice where he was the only Indigenous player. Opposing teams taunted him with slurs.

As a member of the team, Obed had to wear their logo: a red face, skin painted, hair braided. At home games, fans in headdresses bellowed faux-Indigenous chants, and the mascot’s costume was a stereotype of a First Nations chief. “It was incredibly hurtful,” says Obed. Not only were his peers mocking his culture, he says, but they were also using Indigenous customs as a form of entertainment.

That was the early 1990s when Obed had little power to change a team name. Today, he has more sway: Obed is president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, an advocacy organization that represents 65,000 Inuit across Canada. In 2015, soon after his election, the Canadian Football League’s Edmonton Eskimos advanced to the Grey Cup. Obed had long believed that Edmonton’s club, much like his high school hockey team, had no business calling themselves by a name that many consider being a racial slur. Now that he was a cultural leader, he figured it was his duty to speak up.

A few days before the big game, Obed wrote an op-ed for The Globe and Mail in which he implored the team to rebrand, explaining that most Inuit no longer call themselves by that name. Some never have. “It isn’t a term we use to describe ourselves in our language,” he says. “We have always been Inuit.”

The origins of the E-word are unclear. It’s possible that French explorers borrowed the term from the Algonquin ayas̆ kimew, meaning one who laces up snowshoes. It could be adapted from a Cree word that describes eaters of raw meat. Or missionaries might have coined it from the Latin word excommunicati, which refers to non-Christians. Throughout the 20th century, government officials and anthropologists used the word to deride Inuit in the courts, calling them unhygienic, unintelligent, and lazy. The term was and still is, used as a racial slur.

In the 1890s, when Edmonton’s team was known as the Edmonton Rugby Football Club, a Calgary sportswriter used the E-word to mock them because they hailed from a frigid northern city. The team ended up embracing the term, formally renaming themselves in 1910.

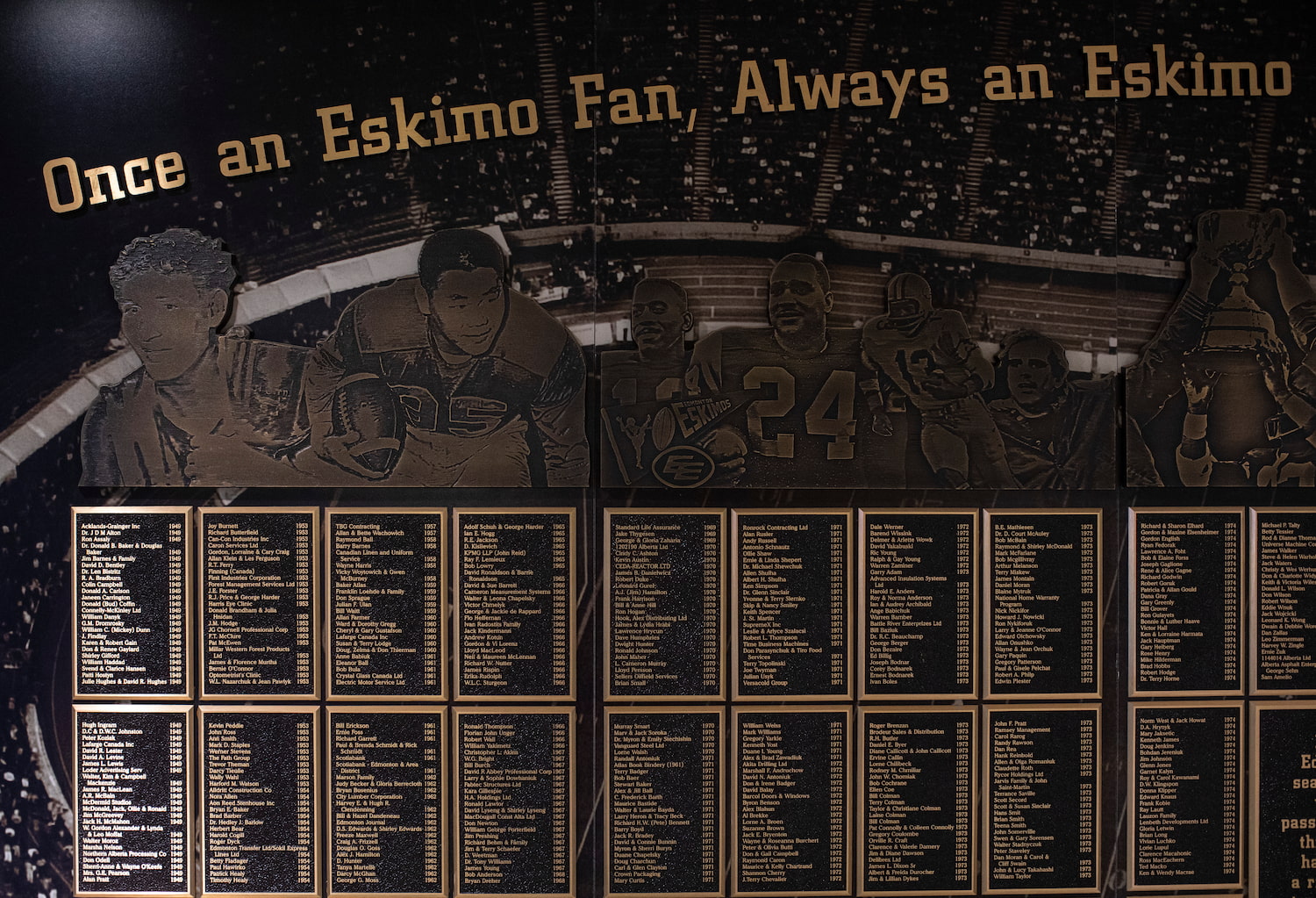

Throughout the 20th century, while the Edmonton club was playing football, real Inuit were facing inhumane treatment at the hands of the government. When the Supreme Court first ordered the feds to administer health care to Inuit, officials struggled to spell and pronounce their names. So, in 1940, they introduced an identification system in which Inuit wore numbered leather discs around their necks to access social services.

The feds dropped the dog-tag system in 1971 and replaced it with an equally degrading program, forcing Inuit, who often went by single genderless names, to adopt Christian names. Thanks in part to an error-riddled Life cover story in 1956, Inuit entered the North American imagination as, in the magazine’s words, the world’s last “Stone Age survivors.” In 1980, Indigenous people from across the Arctic formally agreed to call themselves Inuit and, in effect, drop the name that had been foisted upon them.

Edmonton won the 2015 Grey Cup, but they couldn’t vanquish the controversy surrounding their moniker. Obed’s op-ed turned the team’s name into a matter of national concern. Around the same time, Murray Sinclair, the head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, called for other sports organizations—most notably the NFL’s Washington team, which also used a racial slur in their name—to rebrand. Justin Trudeau, then-Alberta Premier Rachel Notley and the mayors of Edmonton and Winnipeg began coaxing Edmonton’s team to rename themselves. Piles of handwritten letters from schoolchildren arrived at the club’s HQ, agitating for a rebrand. The Inuk throat singer Tanya Tagaq was more pointed, tweeting, “My unpopular opinion is fuck the name Edmonton Eskimos.”

The uproar surprised Len Rhodes, then president and CEO of Edmonton’s football team. At the time, he says, he considered the name to be a respectful ode to Inuit strength and resilience. But he was troubled by the fact that people were offended, and he wanted to start talking about a name change. “I didn’t want the courts and politicians to make decisions for us,” he says.

In 2016, Rhodes invited Natan Obed to Edmonton to discuss the name with senior management. “There was a lot of learning that needed to happen,” says Obed. “There wasn’t a lot of understanding of who Inuit were, where Inuit live, and how Inuit are affected by this moniker.” Soon after, Rhodes wrote a strategic plan recommending that the Edmonton team consider changing their name by 2021. The word was outdated, but the stakes were huge—they had to think about ticket sales, merchandise sales, brand equity. And, so, the proverbial football was kicked down the field.

Rhodes couldn’t have anticipated the way professional sports would transform in that time. In 2016, when Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem to protest racial injustice, millions of fans boycotted the NFL. Today, entire pro sports teams kneel together, and many clubs have refused to play scheduled games, all in solidarity with the social uprising against police brutality and anti-Black racism, especially following the 2020 death of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

In Canada, the recent recovery of more than 1,600 unmarked graves at former residential schools has spurred a similar reckoning with racial justice. But as the nation moves toward progress, it is also stuck with the relics of an unjust past. Administrators and elected officials now have to decide what to do with offensive team names and mascots, statues of slaveholders, and schools named after dead colonizers.

The city of Toronto recently voted to rename Dundas Street, which honours an anti-abolitionist politician. Ryerson University will rebrand, too, owing to its namesake’s colonial legacy. For these institutions, Edmonton’s football team offers a lesson. Changing an offensive name isn’t just about doing the right thing. It’s also about the bottom line.

Most professional sports teams are owned by billionaires —the Dallas Mavericks’ Mark Cuban, the Ottawa Senators’ Eugene Melnyk—or conglomerates like Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment. Edmonton’s CFL team is owned by a collection of local fans and businesses. Those shareholders are represented by a board of nine volunteer directors. The power to change the team’s name ultimately rested with them.

In recent years, the board has consisted of local businesspeople, former players, and lifelong season-ticket holders like Janice Agrios, an Edmonton lawyer. She started attending games as a girl, and her dad served on the team’s board in the 1960s. She joined the board herself in 2013 and later became their first very erupted, she was shocked. “I guess this is an indication that I was ignorant, but I just hadn’t thought about it,” she says. “We needed to educate ourselves.”

In 2017, Rhodes invited Obed back to Edmonton to speak to the board about a name change. “Just bringing it upraised the level of discomfort in the room,” says Rhodes. Obed insisted he wasn’t out to shame the team or chastise their fans; rather, he wanted to instigate change. The board asked if there was anything they could do—engage with Inuit communities, acknowledge Indigenous land, launch special programs—that would allow them to keep the name in good faith. “I was very clear all the way through The name, as a construct, is problematic,” says Obed. If they didn’t change it then, he told them, they’d be forced to change it later. “This was not going to go away.”

At Rhodes’ request, the board set aside funds to consult Inuit about the name. Between 2018 and 2020, team management and a handful of players took several trips to Iqaluit, Inuvik, Ottawa and Yellowknife. They found that Inuit impressions of the name varied wildly. The mayor of Tuktoyaktuk, a longtime fan of the team, said he didn’t mind the name. Meanwhile, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, the director of the seal-hunt documentary Angry Inuk, implored them to drop it. Some Inuit asked why the team hadn’t come sooner. And, according to Allan Watt, the team’s VP of marketing, many others said there were more pressing issues to address, like food and housing insecurity. “And for us to come rolling in wanting to talk about the name of a football team? It’s like, ‘What the fuck are you guys doing here?’” he says.

The PR giant Edelman conducted a survey on behalf of the franchise, which found that eight in 10 Inuit in the Yukon and Northwest Territories opposed a name change. But in northern Quebec and Labrador, where people are less likely to be fans of the team, only a third objected to it.

Meanwhile, non-Indigenous fans seemed largely untroubled by the issue. According to a 2017 Insights West poll, only 12 per cent of Albertans took offense to the team name. Among season-ticket holders, Rhodes says, the number was about the same. A local sports reporter even told Rhodes that fans would run him out of town if he rebranded the team. Tom Richards, a board member who played for the club in the 1980s, fielded complaints from former players. “The guys didn’t like it, but they came to understand why it was happening,” he says. “We were trying to make sure we were doing the right thing and not just reacting to social noise.”

A multimillion-dollar rebrand was not an appealing undertaking. The club had lost $1.1 million in 2019 and were on their way to posting a $7.1-million loss in 2020—the consequence of a season canceled by COVID. After nearly four years of meetings and polling and outreach, the board announced that the team would keep the original name and increase northern engagement—that is, they would send players to Inuit communities to play football, speak at anti-bullying seminars and celebrate local festivals. But, as Obed had warned, the issue did not go away. Days after the murder of George Floyd, the team posted a statement on social media. “We seek to understand what it must feel like to live in fear going birding, jogging, or even relaxing in the comfort of your home,” it read. “We stand with those who are outraged, who is hurt, and who hope for a better tomorrow.” On Twitter, then-Nunavut MP Mumilaaq Qaqqaq slapped back, “If you really ‘seek to understand’ start by changing your team name.” She told APTN News that the team had no right to make money off a derogatory term. “If people won’t listen to us about this issue, how can we expect people to listen to us on bigger items?” Norma Dunning, an Inuk researcher, and professor at the University of Alberta says the decision to keep the name seemed like an affront to Inuit who’d voiced their discontent. “There were just so many people saying how they felt,” she says. “You really have to be willfully blind to ignore that.”

In July of 2020, after years of controversy, Washington’s NFL team promised a “thorough review” of their name. The decision wasn’t just the result of shifting cultural norms. It also revealed the outsized influence of corporate sponsors, who represent millions of dollars in revenue for sports organizations. Washington’s football team was reacting to pressure from Pepsi, FedEx and Nike. Walmart and Target had stopped selling their gear.

In Edmonton, too, it was sponsors that finally precipitated a name change. That same month, Belairdirect, a longtime sponsor of the Edmonton club’s 50/50 draw, threatened to cut ties with the team. “In order for us to move forward and continue on with our partnership….we will need to see concrete action in the near future including a name change,” the insurer stated. The next day, the team announced they would accelerate their name review process.

A week later, the gambling website Sports Interaction, which was in the process of negotiating sponsorship terms with the team, publicly requested a rebrand, too. Sports Interaction is owned and operated by the Mohawks of Kahnawake, a community of 8,000 near Montreal. “We felt a responsibility to do the right thing, probably more so than anyone else,” says Dean Montour, CEO of Mohawk Online, the parent company of Sports Interaction. “We’re First Nations–owned. We’re not like any other major corporate sponsors that Edmonton has.”

Norma Dunning tracked the team’s public sponsorship struggles with interest. “At the end of it all, money talks,” she says. Working with the non-profit Progress Alberta, she created a webpage where, with one click, people could send a blanket email demanding change to 36 of the team’s major sponsors. Nearly 2,000 people participated, flooding partners’ inboxes. Those companies, in turn, started contacting the club’s office, fed up with the deluge. “Our sponsors were getting too many phone calls,” says Tom Richards. “We’re a community-owned team, and corporations are happy to support us. But they’re not in the business of answering phone calls and defending our name.”

The board was in a bind. If they kept their name, they risked losing some of their sponsors, which accounted for roughly $6 million in yearly revenue. If they rebranded, they risked alienating their fans—some of whom had threatened to boycott if the team changed their name—and losing their single biggest revenue stream: more than $8 million in annual ticket sales. But irate fans rarely follow through on such threats. In 2014, Michael Lewis, the author of Moneyball and The Big Short, studied several American colleges that changed their team names because they were considered offensive. He found that revenue remained stable in the year following the rebrand and then increased in subsequent years. “Threats of the boycott are empty,” he wrote in The New York Times. Refusing to shed a problematic name, he added, “borders on managerial malpractice.”

In late July of 2020, Edmonton’s football team announced they would rebrand. By then, the board had discussed the issue at every meeting for four years straight, says Richards, and it was time to move on. To them, it seemed like the right thing to do, both morally and financially. “It got to the point where it made sense to put this behind us and not have our stakeholders deal with this,” says Richards. “It had become a big, big distraction.”

The team suddenly had a new problem: They needed a new name. In November 2020, the club canvassed its fans for ideas. They received more than 14,800 submissions. After consulting Oxford English Dictionary experts and University of Alberta linguists—team leadership couldn’t decide whether to add an “s”—they settled on Elks, a close cousin of the team’s former nickname, the Esks. David Beard, a player who visited Inuvik as part of the team’s outreach, was pleased with the new moniker. “It changed one letter in the grand scheme of things,” he says. “It’s the same colours, the same community. It will not change the brand of football we play.”

By then, Len Rhodes had left the team to run for provincial office; he lost and later took the top job at Alberta Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis. In his absence, Allan Watt took ownership of the rebrand. “It was not an easy process,” he says. “There was no handbook on rebranding. We couldn’t open to page 64 and say, ‘Here’s what you do in this instance.’”

First, the team trademarked the new name, formally reincorporated the business, and registered a new URL. Then they hired the advertising agency DDB to create a logo. Watt wanted it to be modern yet iconic and versatile enough to appear on jerseys, helmets, football fields, keychains, hats, socks and beer cozies. More than anything, it had to be cool. “We want kids to want that logo on their pyjamas,” he says. Watt and the board saw hundreds of sketches before deciding on their two logos: a green-and-gold elk head and a football enveloped by antlers. The team then worked with their apparel manufacturers to create new equipment and merchandise. They also began furtively updating their Commonwealth Stadium to include massive new murals, dozens of green-and-yellow flags, and a gargantuan 60-meter-long elk head painted on the field. “We had no idea the amount of rebranding that was necessary,” says Watt. “I’m sure we’ll keep finding the old name tucked away in places we had no idea it was.”

Between the new logo, fresh gear, the stadium overhaul and sundry administrative changes, Edmonton’s CFL team spent roughly $2 million on the rebrand. “In the short term, yes, it was an expense,” says Rhodes. “But in the long term, I believe the return on investment will be at least tenfold.” In the wake of the rebrand, merchandise sales spiked. Instead of boycotting the Elks, fans stormed the team store, which had to extend its hours to meet demand. By the end of August, the team had sold as much merch as it normally moves by November.

Sponsors applauded the change, and uneasy fans returned to the team with a clear conscience. Matthew Belton, a longtime supporter who started an online petition in 2015 asking that the club change its name to the Elks, was relieved when he heard about the rebrand. For years, he felt apprehensive about cheering for the team. “It’s like when you have a good friend with some bad qualities—you just let it slide,” he explains. “I’m happy that when I take my kids to football games now, I won’t have to explain what that word means.”

At the Elks’ home opener this past August, the team handed out free T-shirts to tens of thousands of fans as they filed into the transformed stadium. Antlers appeared on cups, on advertising panels, on the press box and on the jumbotron. The coaches wore in Elks jackets and carried Elks playbook binders. Of course, the most noticeable change was on the field: Players in yellow helmets and newly designed jerseys rushed onto the turf through an Elks-branded tunnel. When the team sacked the opposing quarterback, its players held their hands to their ears like antlers and galloped in celebration. The transformation was complete.

This past May, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced that 215 children’s remains had been located at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. Within a couple of months, some 1,600 unmarked graves were found across the country, and many Canadians began re-examining the country’s relationship with Indigenous people. By that point, Edmonton’s football team had already dropped its old name. Ryerson University had not. Like the Edmonton team, the Toronto institution had faced criticism for years. Its namesake, Egerton Ryerson, influenced the creation of the residential school system, created legislation that segregated Black kids into their own institutions, and believed that girls should not advance beyond elementary instruction.

The school acknowledged Ryerson’s dark legacy with a statement in 2010 but didn’t entertain the idea of a rebrand. In 2017, as the university celebrated Canada’s sesquicentennial, the student union and Indigenous students’ association formally requested that the school change its name and remove the statue of Ryerson from campus. The following year, the school’s own truth and reconciliation report stated that “the name of the university is a significant barrier that must be acknowledged and addressed in a more fulsome manner.”

By the summer of 2020, patience was wearing thin. More than 10,000 people signed a petition asking for a name change. In response, the university created an annual powwow event introduced an Indigenous-languages course, hired more Indigenous faculty, increased education about colonial history, placed an explanatory plaque beside the statue of Ryerson and commissioned a task force to probe the school’s relationship with Indigenous people—it did everything short of changing the name. Anne Spice, an assistant professor of Indigenous environmental knowledge and a Tlingit member of the Kwanlin Dün First Nation, says that even in early 2021, a name change didn’t seem to be on the table. “It was frustrating to see the institution drag its feet on this,” she says.

Then the children’s bodies were recovered, and the university could no longer rationalize the Ryerson name. In August, the school’s task force recommended changing it, among other actions aimed at respecting Indigenous people and history. The university accepted all of its own recommendations, and a new name is now on the horizon. “Indigenous faculty, students, and staff have been talking about this for a long time, but it wasn’t taken up until the university looked bad,” says Spice. “It shouldn’t take the recovery of children’s graves for us to be treated with respect in the places we work and study.”

Ryerson and the Elks are the exceptions, not the rule. Across the country, schools, statues, teams, streets and entire towns bear names that venerate ugly aspects of Canada’s national identity. To those with the power to change them, Natan Obed offers the same advice he gave to Edmonton’s CFL team six years ago: They can defend their institutions’ history, consult Indigenous people, form task forces, hire PR firms and conduct online surveys, or they can save time, money and heartache and simply act. The issue will not go away. To wit: his high school hockey team. In 2019, Maine became the first state to outlaw Indigenous team names, mascots and logos. More than three decades after Obed first laced up his skates, his former hockey team is now known as the Coyotes.